Asymmetry and Injury Risk

One of the unique features of dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is its ability to provide accurate and reliable segment analysis of the body. Our Dexalytics software allows you to take the segment analysis and identify muscle mass asymmetries.

What is asymmetry and why measure muscle imbalance?

Asymmetry in muscle mass is normal in athletes and often develops in rotational athletes (track and field, baseball) or athletes that have a consistent pattern of movement (offensive or defensive linemen). An asymmetry in muscle mass does not mean an athlete will be injured; however, it can be a risk factor for injury. Importantly, if you have baseline data, muscle asymmetries can be important to track during return to play scenarios or just in examining an athlete's changes in body composition with training. Dexalytics measures leg, arm, and in some cases trunk asymmetry and alerts you when an athlete reaches a specific level. This alert allows you to take a closer look at that athlete to determine if any intervention is necessary.

We often see asymmetries in athletes and without any symptoms, these asymmetries may be normal. Offensive linemen, hurdlers, and pitchers are individuals with common asymmetries. However, an asymmetry that develops due to an injury or after an injury can be another story. A leg that has been immobilized due to injury often loses muscle mass, which can lead to muscle imbalances. By monitoring asymmetry, athletic trainers and strength coaches can devise a program to minimize this imbalance and reduce the chance of the athlete injuring the leg or arm again.

Finally, asymmetries can also occur between upper and lower body mass. In the majority of sports, the lower body is supporting the upper body during movement. The requirements of that athlete’s sport will influence the upper to lower body ratios. These ratios can be a good way to compare the distribution of mass between players at the same position that may be different heights. Moreover, these ratios can be used to examine long-term trends in how an athlete’s body is changing and where that change in mass is coming from. For most athletes, you’d want increases in the lower and upper body but over time we have seen increasing upper to lower body ratios that signal a loss of lower body mass or a disproportionate increase in upper body mass.

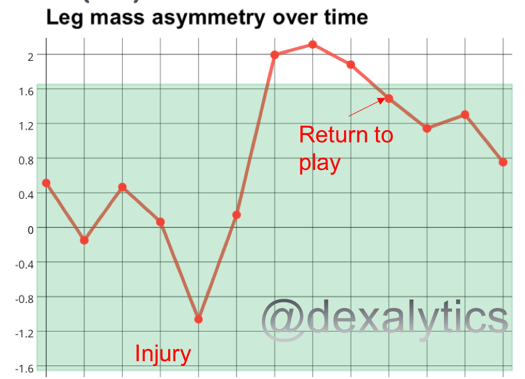

Injuries are multifactorial and muscle asymmetries are not always associated with injury. However, understanding each athlete’s normal mass distributions (e.g. asymmetrical to one side) can be a key factor in determining "normal" asymmetry vs. "at-risk" asymmetry. In the image below we see an example of this. The player's legs are fairly symmetrical, but then a larger asymmetry develops and an injury occurs. During the recovery period the legs are monitored and, even after returning to play, there is still an abnormal asymmetry pattern. The bottom line is some asymmetry in muscle mass is normal and, in some athletes, it is to be expected. However, it is important to track asymmetry to possibly prevent injury or guide an athlete in recovery from an injury.

About the Author: Donald Dengel, Ph.D., is a Professor in the School of Kinesiology at the University of Minnesota and is a co-founder of Dexalytics. He serves as the Director of the Laboratory of Integrative Human Physiology, which provides clinical vascular, metabolic, exercise and body composition testing for researchers across the University of Minnesota.

About the Author: Tyler Bosch, PhD is a Research Scientist in the College of Education and Human Development at the University of Minnesota, and is a co-founder of Dexalytics.